As we observe Mother’s Day this year there is one fact that often escapes notice. For more than three hundred years, most mothers in the Americas were enslaved Africans. These women gave birth to generations of children fathered by African, European, and Indigenous men. In “Middle Passage Enforced Migration,” Paul Lovejoy states that “From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the great majority of people moving from the Old World to the New World were black people. When gender is taken into consideration, then it can be said that far more black girls and women were forcibly taken to the Americas than the number of European girls and women who migrated, at least before the middle of the nineteenth century.”

By social and legal precedent, the children of these African women created wealth as property and human resource. In order to maintain a North American society based on racial hierarchy and European dominance, it was crucial that the “one drop rule” be enforced and a child’s legal status be determined by that of the mother. In fact, Thomas Jefferson, founding father and drafter of the Declaration of Independence, explicitly advises his fellow-citizens to establish and protect their wealth by the purchase of land and female captive Africans.

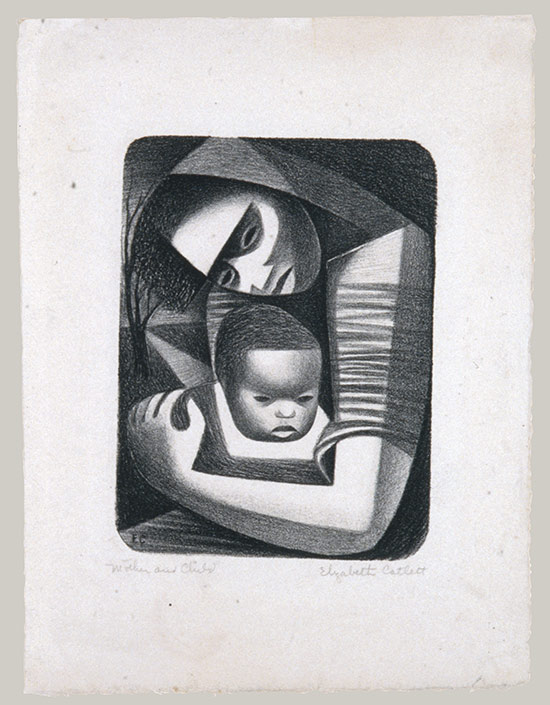

Deprived of the rights and privileges of motherhood, many enslaved women seldom had the opportunity to protect and raise their own children. The narratives of enslaved mothers are replete with suffering, horror, separation, and injustice. Yet, enslaved mothers were nurturers of America’s children – the offspring of others and their own when possible. They transmitted and adapted vestiges of their individual ethnic cultures throughout the diaspora. “Furthermore, people of African and Native American origins intermingled, generating composite and dynamic communities that owed little if anything to European influence” (Lovejoy “Middle Passage”). Grounded in American culture, to this day Black women symbolize caretakers in this nation.

Although there was a “relative scarcity of females [in the Americas], enslaved women often constituted the majority, sometimes the overwhelming majority, of available women for procreation. The movement of people of African descent to the Americas was a central dynamic of the resettlement of the Americas after the disastrous decline in the Native American population” (Lovejoy “Identity in the Shadow of Slavery”). No matter our individual perception, the truth is there is no ethnically pure person anywhere on this land. Acknowledging this history, former Louisiana governor Huey Long’s quip, “… a nickel’s worth of red beans and a dime’s worth of rice would feed all of the pure whites…” is certainly appropriate. Most Americans are descended from or related to someone of African descent. We have ancestors who took part in this history. This is not a rationale of dilution but an acceptance of reality. We are so conditioned by a racial caste system that we often fail to envision ourselves as residents where people have a shared heritage spanning almost 500 years – since 1526.

We owe our maternal ancestors honor and a debt of gratitude. Wherever they were transported and held in bondage, these women “found ways to express themselves, and despite the oppressive conditions, Africans and their descendants reestablished old practices and formulated new communities in which religious expression, music, and folklore had a prominent role, prompting a series of cultural renaissances in Brazil, Cuba, and elsewhere” (Lovejoy “Identity”).Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project commemorates all mothers on this special day.